Imagen: Joachim S. Müller

Common Swift

Apus apus

Swifts are of the order Apodiformes, of the family Apodidae. Apipodae, is one of the oldest families in the natural world, it was separated from other birds probably in the Tertiary period 65 million years ago. They are evolutionarily advanced and developed for flight.

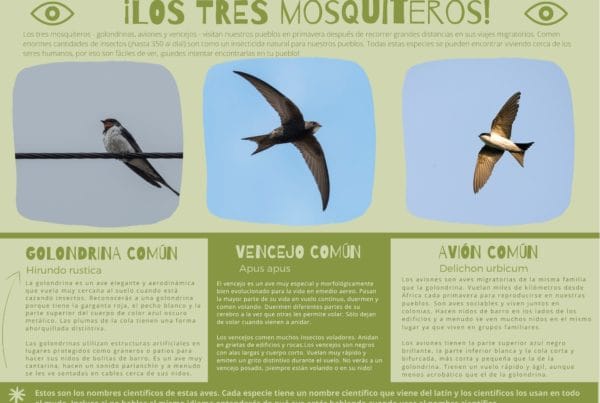

Superficially they are similar in shape to swallows and house martins, all are insectivorous birds but they are not remotely related. The ancestors of modern swifts developed at least 45 million years ago compared to swallows about 3 million years ago. The similarities are due to a phenomenon known as convergent evolution, when animals occupying the same ecological niche end up resembling each other even though they were born from different systems because they have adapted to the same environment, in this case catching insects in flight.

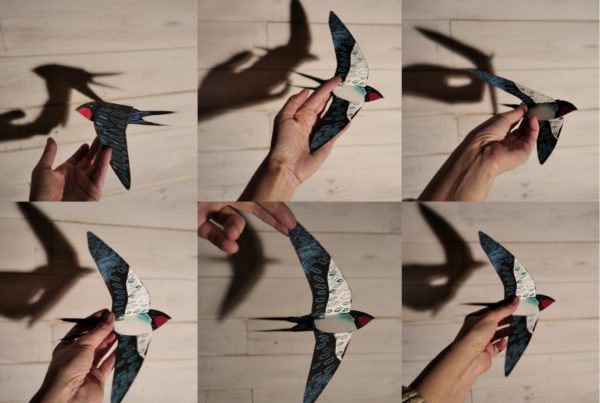

Swifts are black / brown with a pale gray spot under the chin. They have a compact physical appearance, a short forked tail and long thin wings in a crescent shape. They have a unique morphological characteristic of two opposing toes, which means that they can cling to vertical surfaces but cannot perch. Swifts spend months in continuous flight, sleeping, feeding and reproducing in the air only stopping when they nest to breed.

They have a very fast flight, it has been recorded that they fly at speeds of 112km/h. As a group they are the fastest birds in level flight, the Peregrine Falcon is faster but only during stoop, the descent made when it dives in search of prey, not in level flight. After leaving the nest, a swift will continue to fly almost non-stop for two or three years until it reaches breeding maturity.

They have a distinctive scream in flight, a repetitive shriek, this being a form of communication in hunting groups.

Feeding

Swifts feed on a wide variety of flying insects; aphids, wasps, bees, ants and flies, and an abundant supply of insects is essential for their survival. Swifts eat an enormous amount, a dietary requirement of such an energetic life. They hunt insects in a range of habitats from grasslands, open waters and over forests, to the skies above towns and cities. They fly in groups in insect-rich areas, such as wetlands, attracted by swarms of insects.

Swifts navigate through weather systems often traveling great distances to circumnavigate clouds and rain to find food. In studies of swift behavior during bad weather, a 900 km round trip has been recorded to search for abundant insects elsewhere. They keep insects in their throat by using a product from the salivary glands, to form a food boll. Parental swifts collect up to 1000 insects at a time to carry them to their chicks. When there is an abundance of food they can catch a lot and then go for days without eating if there is no food.

Breeding

Swifts form pairs that mate for years, returning to the same nesting site to associate year after year. Swifts have a remarkable way of surviving bad weather and food shortages, their eggs surviving by cooling down at any stage of their development if the adults have to spend more time away from the nest looking for food, something that would kill the embryos of any other bird. The development of the egg will simply slow down until one parent returns. Bad weather can prolong incubation for four or five days. Similarly, young chicks are able to enter a torpid state, lowering their metabolic rate and surviving on their energy reserves for days while the parents leave them to hunt. A young swift will stay in the nest for 40 - 45 days, once it leaves the nest it will fly away immediately and be totally independent.

Imagen izquierda: “20080905_050 叉尾雨燕 但尾羽有一邊斷掉了” by pseudolapiz is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

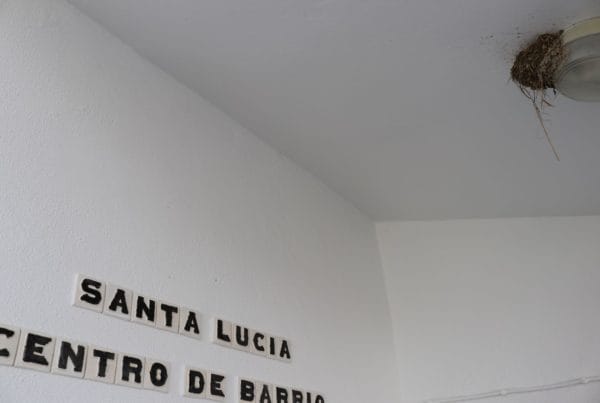

Nesting

Originally swifts nested in tree burrows or holes in cliffs and have adapted to live in human structures. They build their nests with airborne material trapped in flight as they do not descend to the ground, which is molded with their saliva. They generally choose high sites for their nests since they enter their nesting holes with direct flight, and take-off is characterized by a free-fall descent. They nest in holes, under tiles, in holes under window sills, under eaves and gables and are loyal to their nesting sites each year.

Migration

Swifts migrate to Africa in winter following various routes, ending up in equatorial and subequatorial Africa. The migrations are influenced by wind patterns. Smaller passerine birds stop to rest and refuel during their migrations, while swifts have an entirely aerial migration using a flight strategy that allows them to reach average migration speeds well above 300 km/day which is much higher than what is possible for similar sized passerines.

It was generally proposed that swifts cross the Sahara on a broad front, but recent tracking using miniature geolocators revealed a substantial deviation from the migration routes indicating that they avoid the Sahara desert in its widest parts.

Swifts spend three and a half months in Africa and a similar time in their breeding grounds; the rest is spent flying. Non-breeding swifts and sexually immature birds are the first to leave their breeding area. The breeding males follow, and finally the breeding females. The breeding females stay longer in the nest to rebuild their fat reserves. The time of departure is usually determined by the light cycle, and begins on the first day with less than 17 hours of light. For this reason the northernmost birds leave first The birds use the low pressure fronts during their spring migrations to exploit the southwest flow of warm air, and on the return trip, they ride the northeast winds on the back of the low pressure fronts.

The geo-tracking of a Spanish Swift studied in the Migra program traveled from Madrid 9000km in two months to reach its wintering sites in Africa.

Threats

The threats of predation are minimal due to their aerial dominance, although swifts are hunted by hawks and sparrowhawks. Their choice of high nesting sites on vertical surfaces is also an advantageous tactic to avoid predation. Other threats include decreasing insect populations due to the use of pesticides and air pollution in urban areas. The loss of nesting sites due to building renovations and the lack of availability offered by new construction has affected swift populations. Swifts are listed in the National Catalogue of Threatened Species as "Of Special Interest".

References / Further Reading

Annual 10-Month Aerial Life Phase in the Common Swift Apus apus. Read here.

Phylogeny of Early Tertiary Swifts and Hummingbirds (Aves: Apodiformes) Read here.

How swift are swifts? Read here.

Apus apus, common swift. Read here.

Annual 10-Month Aerial Life Phase in the Common Swift Apus apus. Read here.

Swifts; breeding and nesting habits. Read here.

¿Donde están nuestros vencejos en invierno? Read here.

Hole selection by nesting swifts in Medieval city walls of Central Spain. Read here.

Migration Routes and Strategies in a Highly Aerial Migrant, the Common Swift Apus apus, Revealed by Light-Level Geolocators. Read here.

Swift Conservation.